Jewish Studies library: restitution of loot

16 Sept 2025

With the return of a stolen Hebrew textbook to the Jewish Congregation, LMU’s Jewish Studies department is addressing historical Nazi injustice.

16 Sept 2025

With the return of a stolen Hebrew textbook to the Jewish Congregation, LMU’s Jewish Studies department is addressing historical Nazi injustice.

Torah ye-hayim – that is the title of a booklet in octavo format, which Professor Ronny Vollandt handed over to Charlotte Knobloch on 2 September 2025. The President of the Jewish Congregation of Munich and Upper Bavaria (IKGM) was moved: “How could I not be? This is unbelievable!” she said as she leafed through the Hebrew textbook.

The book once belonged to the Jewish elementary school (Israelitische Volksschule) in Munich – where Knobloch, then called Charlotte Neuland, started school in 1938 for a brief period and which was part of the Jewish Congregation.

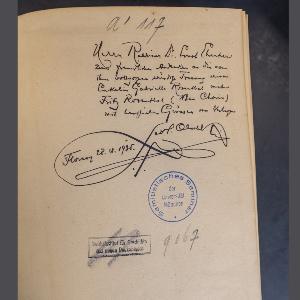

Vollandt also brought Paleografia Ebraica by Florentine scholar Carlo Bernheimer to St.-Jakobs-Platz in Munich, to show the president what other treasures the Jewish Studies library held. This book also stirred personal memories in Knobloch. It contains a dedication skillfully executed in Gothic handwriting: Bernheimer’s work was a thank-you gift from Italian Romance philologist, antiquarian bookseller, and publisher Leonardo Olschki to Rabbi Dr. Ernst Ehrentreu for the marriage of Olschki’s granddaughter Gabriella Rosenthal to the subsequently renowned Munich religious scholar and journalist Fritz Rosenthal – better known as Schalom Ben-Chorin.

“I remember Rabbi Ehrentreu preaching at the pulpit of the synagogue in Munich,” says Charlotte Knobloch. And she also recalls Gabriella Rosenthal being a “stunningly beautiful woman.”

The dedication by Leonardo Olschki to Rabbi Ernst Ehrentreu. The crossed-out stamp refers to the Reich Institute for the History of the New Germany. | © LC Productions/LMU

Before being returned to the Jewish Congregation, Torah ye-hayim, which means something like “Torah of life,” was part of a collection of some 200 works located in the Jewish Studies holdings at LMU’s Institute for Near and Middle Eastern Studies. The collection also contains Paleografia Ebraica.

And what is special about these books on literary, historical, and religious topics? The Nazis stole them. To this day, they are disfigured by the stamp of an eagle and a swastika. Their proper owners came from all over Germany – from Stettin, Königsberg, Berlin, Munich. At least, this can be ascertained for the works that contain owner’s marks, ex libris labels, or dedications.

Such as the bible of Moritz Schiel, in which we see the affection of his mother on the occasion of her son’s wedding. Aside from this dedication, the only information we have about Schiel himself is the scanty details held by the Central Database of Shoah Victims’ Names at the Yad Vashem remembrance center: that he was born in 1860, died in 1942 in Theresienstadt, and that he lived in Hildesheim before his deportation and murder. And some books have no markings at all other than the Nazi stamp and will probably never be returned to their rightful owners or their descendants.

A sense of duty to confront Germany’s Nazi past was one of the primary motivations for Ronny Vollandt and his colleague Sarah Lemaire to pursue the systematic recording of the books and research into their former owners and their descendants. Books without identifying marks, or for which there are no descendants, are entered in the Lost Art database.

Lemaire has spent a lot of time over the past 20 years searching for the descendants of people like Schiel. She emphasizes that she and a colleague “started out with a certain euphoria that we’d be able to return the books soon. It’s a real pity we haven’t been able to restore a single book to its rightful owner yet apart from the textbook.”

Like the six works from the library of Rabbi Hermann Vogelstein, who was active in Königsberg (modern-day Kaliningrad), among other places, and whose grandchildren – one who also bears the first name Hermann – Lemaire managed to locate in the United States. Unfortunately, her email looking to establish contact and return the books remained unanswered. “As much as anything else, we’re just much too late,” she says.

Nevertheless, Lemaire was able to learn some things about the life of the rabbi, who died in 1942 in New York. His sister had written an autobiography, in which she describes the fate of her brother and his family.

In fact, Vogelstein did not want to leave Germany and would have rather gone to the concentration camp with his congregation. Only the “emotional blackmail” of his wife, who also wanted to stay, induced him to flee via England to the United States, where he died a short time later. According to the autobiography, leaving his library behind must have been very painful for him – a tiny bible was all he took on his journey into exile.

To explain how the books ended up at LMU, we must start with the Reich Institute for the History of the New Germany. Founded in 1935 by historian and LMU alumnus Walter Frank in Berlin, the institute had offshoots in Frankfurt am Main and Munich – the so-called Institute for Research on the Jewish Question. The Munich branch had close geographical and staffing connections to LMU.

“The institute was the attempt by the National Socialists to scientifically underpin their antisemitic propaganda,” says Ronny Vollandt. “It was for this purpose that they established a library with books from Jewish cultural contexts.” The goal of the institute, Vollandt explains, was to provide the legitimation for discrimination, expropriation, expulsion, and extermination. He is also convinced that particularly valuable pieces – such as precious Torah scrolls – were sold to procure foreign currency after being stolen.

Dr. Sven Kuttner, Head of Special Collections at the University Library, reckons that the book collection was primarily about prestige, to give the institution a scholarly gloss. “This had little impact on the fundamentally antisemitic orientation of such institutions. Dyed-in-the-wool Nazis do not need any books for their worldview,” emphasizes Kuttner.

Under the aegis of Kuttner, incidentally, the University Library was one of the first libraries of its kind in Germany to undertake an inventory of its holdings of stolen books. This project, which began at the end of the year 2000, has had to process no fewer than 14 linear meters of such works.

Kuttner suspects the books relating to Judaism probably took the very short trip from the Historicum to the Semitic Studies department. Franz Schnabel, who took over the Chair of Modern History at the Historicum in 1947, was acquainted with Professor of Semitic Studies, Anton Spitaler. “It’s quite possible that Schnabel gave the books to Spitaler because of their subject-matter – but without documenting it,” conjectures Kuttner. “In any case, there are no records of such a transfer.”

It has been possible to restore only a few books to date, among them some works that were sent to a family in Tel Aviv. The grandparents had met a violent death during the Shoah. “For descendants, these restitutions can be very meaningful, as a book can be the last material point of connection to their murdered relatives. As such, books also play an important emotional role,” observes Kuttner.

Library managers effectively reversed the role of victim after the war and cultivated the narrative that they were the victims as a result of all the books destroyed in bombings. In this way, they were able to sweep their own responsibility under the carpet.Dr. Sven Kuttner

For many directors of the University Library in the postwar years, however, this aspect and dealing with the provenance of the books were not a concern, says Kuttner – even though it was well known there were books in the library which had been stolen from their Jewish owners.

What is more: “Library managers effectively reversed the role of victim after the war and cultivated the narrative that they were the victims as a result of all the books destroyed in bombings. In this way, they were able to sweep their own responsibility under the carpet,” notes Kuttner.

It was not until the 1980s, he explains, that young researchers began to address this issue and make records of stolen books – partly against the resistance of older colleagues.

Today there are standardized procedures for recording books and established practices, which Vollandt, Lemaire, and Kuttner have applied, for returning the works where possible. When this is not the case, because there are no descendants or institutions as legal heirs, the books are registered in the Lost Art database in Magdeburg.

Books that could not be restored to their owners are kept in the Historicum’s shelving facility under stringent conservation conditions. Perhaps some of them will yet be restored to where they belong: the descendants of Nazi victims.

The aforementioned Reich Institute was not the only route by which stolen books entered the library. So-called secondary loot also found its way into the library’s holdings after the war in the form of purchases from the antiquarian book trade – to replace missing books, for instance. “Antiquarian booksellers were generally not overly concerned with the provenance of books,” explains Sven Kuttner.

Many books also changed hands for large sums at auction. Profit-seeking attitudes to loot are illustrated by the case of an over 500-year-old bible, which was originally owned by Munich Rabbi Cossmann Werner and belonged to the Jewish Congregation of Munich and Upper Bavaria.

Nazi raiding parties stole the precious work during the Kristallnacht pogrom on 9 November 1938. Large parts of Werner’s library and other stolen books, which had been returned by the municipal library in the 1950s, were destroyed in an arson attack on the Jewish Congregation’s building at 27 Reichenbachstraße in 1970, in which seven Jewish people also lost their lives.

In an interview with the Jüdische Allgemeine newspaper in 2020, Charlotte Knobloch said that as a consequence of the fire, “the few books from the library that are still in circulation somewhere on the so-called free market have become even more valuable for dubious collectors.”

Indeed, Cossmann Werner’s bible was up for auction in Munich on 7 November 2020. As if the choice of date – two days before the anniversary of Kristallnacht – were not tasteless enough, the starting price of 15,000 euros for a stolen work was the height of unscrupulous profiteering. However, a member of the congregation was able to come to an arrangement with the auction house. The bible did not make it to auction and was bought by this individual to eventually be displayed in the synagogue as a permanent loan.

The first step for me when dealing with a historical manuscript, a source, is always to ascertain its provenance: Where does the source come from? Which paths has it taken to get here?Prof. Dr. Ronny Vollandt

Ronny Vollandt confirms these practices in the art object trade and emphasizes the role of the researcher in this context: “The first step for me when dealing with a historical manuscript, a source, is always to ascertain its provenance: Where does the source come from? Which paths has it taken to get here?”

In the field of Near and Middle Eastern Studies, this due diligence is all the more important in light of the highly volatile and politically dangerous circumstances that currently prevail: “A few years ago, Jewish manuscripts from an Afghan context showed up in a collection in London. In such cases, the provenance is difficult to clarify,” says Vollandt. His policy is therefore: “I don’t engage academically with such sources. I don’t want my research and publication of the results to cause these writings or text fragments to appreciate even more in value. In that way, I’d just be encouraging the black market.”

To make students more aware of this problem, he is an advocate for enshrining provenance research in university teaching. The department has already held a seminar that addressed provenance research, flanked by a tutorial on Nazi loot in the Jewish Studies library. “We also want to devise exhibitions that will be curated by students. This is a very effective way of integrating this complex of issues into teaching.”

Charlotte Knobloch welcomes the initiative of the Jewish Studies department to return the books. And she emphasizes: “A lot more could be done. There are no doubt many cultural objects that we’re unaware of.” She fears that otherwise generations to come could have no appreciation of the issues surrounding the stolen cultural artifacts.

She hopes in any case that the booklet which she can now hold in her hands and which she intends to give pride of place in the Jewish Congregation could be a little highlight of an exhibition. In a meeting with Ronny Vollandt, the president has already sounded out possibilities for exhibiting the books in a larger context and identifying institutions that could be suitable partners – so that the books and the people who once owned them are not forgotten.

Read also: Lost books, stolen home